From amazingly colorful antique relics to the attempts to standardize colors in biomedical imaging – color is gaining in relevance in the sciences. The history of the ontology of color has already gained some attention in history of science. It is of course not to disentangle from its meaningful use or non-use. Yet the epistemic role of color, its long-standing neglect due to historic symbolic, in part gendered, ascriptions, and the function of color in visualizations for internal scientific use have not received much attention in the sciences and humanities to date. This is especially the case for non-mimetic color use where color is not meant to copy nature, but rather carries implicit or explicit symbolic meanings. This session focuses on the meaningful interpretation and application of color by the sciences – in historical perspective and across disciplines. How was color and the use of color understood, what did/do specific colors mean, how did this change?

The Meaning Of Color in the Sciences (Public event)

09.30 Registration, Welcome address & Coffee

Chair: Bettina Bock von Wülfingen (HU Berlin/Image Knowledge Gestaltung)

10.15 Sophia Roosth (Department of the History of Science, Harvard University)

Spectral Analysis of the Specters of Life: Molecular Ecology, Microbial Mats, and the Origins of Life

10.45 Alma Steingart (Department of the History of Science, Harvard University)

Mathematics on the Spectrum

11.15 Coffee break

11.30 Michael Rossi (Department of History, University of Chicago)

»Green is Refreshing«: Color and Healing in Nineteenth Century Medicine

12.00 Alexander Nagel (Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, USA)

Research on Color Matters: Towards a Modern Archaeology of Ancient Polychromies

12.30 Lunch

Registration for the public event until 20th of June via email to Florian Bodewald

For any further question please approach the organizer Bettina Bock von Wülfingen

Poster

Sophia Roosth (Department of the History of Science, Harvard University)

Spectral Analysis of the Specters of Life: Molecular Ecology, Microbial Mats, and the Origins of Life

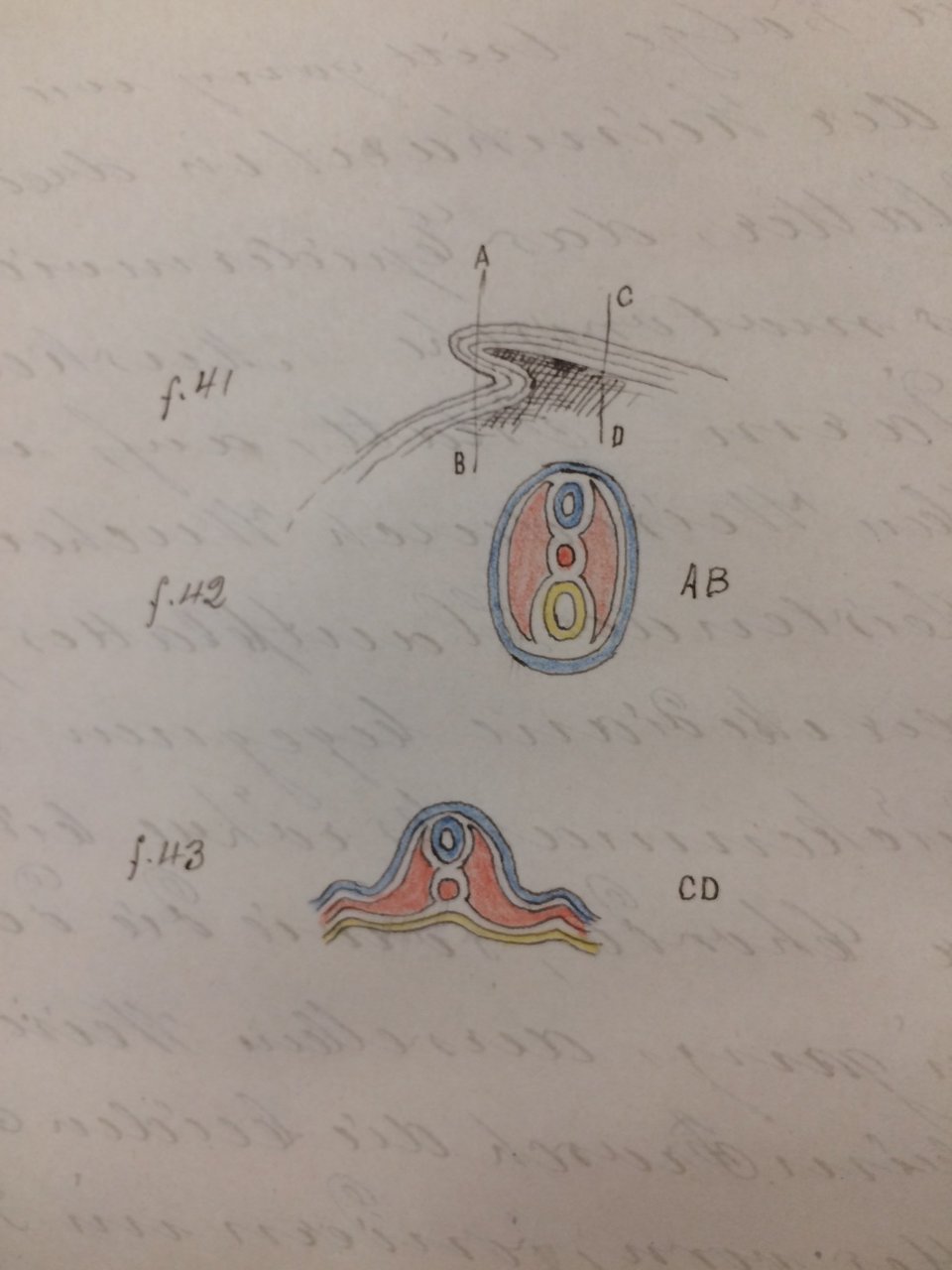

The colors of a charismatic living thing called a »microbial mat« are proxies that allow geobiologists to imagine the ancient atmospheric conditions in which life first formed. In this talk, I report on geobiological research into modern microbial mats, which are entities somewhere between an ecosystem and a metaorganism. Microbial mats are three-dimensional, densely interconnected symbiotic communities constituted by billions of single-celled microorganisms. Since the early 1980s, geobiologists have recognized that stromatolites, the oldest known fossils on Earth, could be the petrified remains of these living communities. While living microbial mats are relatively rare today, they once covered most of the ancient Earth (the oldest identified is 3.7 billion years old). Importantly, mats are polychromatic, each color testifying to a different microbial lineage capable of metabolizing a different chemical. A thin line of electric green coats striated layers of russet, brick red, and deep plum. Studying modern-day microbial mats therefore offers geobiologists a glimpse into ancient environments, even to the possible origins of life on Earth.

Alma Steingart (Department of the History of Science, Harvard University)

Mathematics on the Spectrum

In his posthumously published »Remarks on Color«, Wittgenstein writes that mathematics and color can be seen as models for one another. His remarks are neither about color as psychology nor phenomenology. Instead he writes, »here we have a sort of mathematics of color« (in his Remarks on Color). In this talk, I turn to the beginning of the twentieth century to ask to what degree do mathematics and color represent similar epistemological difficulties? I suggest that mathematical and chromatic propositions pose analogous philosophical problems precisely because their epistemic status can be reduced to neither objectivity nor subjectivity, neither logic nor empiricism. Both, I suggest, challenge us to ask what it means to know.

Michael Rossi (University of Chicago)

»Green is Refreshing«: Color and Healing in Nineteenth Century Medicine

Among the many meanings of particular colors in the European and American medical literature of the early 19th century, the color »green« was especially associated with qualities of healing, recuperation, and rejuvenation. From manuals on best nursing practices, to treatises on workplace health, to advice for better living, expert and popular healers alike tended to subscribe to the commonplace wisdom that the color green was a salubrious and efficacious way of reviving both flagging spirits and ailing bodies. This paper examines the symbolic, semantic, and practical dimensions of the color green in nineteenth century medicine — from its mimetic associations with nature and growth, to its place in formalizing otherwise occult physiological processes, to its role in regulating visual and bodily health and conduct. Ultimately, the healing properties of the color green for nineteenth century medical practitioners comprised part of a larger attempt to describe a novel relationship between mind and body, and science and sensation. This relationship was required at once to preserve the common-sense distinction between imponderable soul and material corporeality, while allowing for novel epistemologies of the sensing, feeling, thinking body – including (but not limited to) physiology, psychophysics, and (eventually) biomedicine.

Alexander Nagel (Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, USA)

Research on Color Matters: Towards a Modern Archaeology of Ancient Polychromies

Periodically, throughout the last two hundred centuries, museums allowed for visitors' imagination to experience the colorful ancient environment. Installations in London, Paris, Munich and Washington, DC until the 1920's and in more recent decades made references by displaying colorful and often very creative reconstructions, and the museum visitor appreciated being educated about the polychrome pasts of ancient Egypt, Greece and the Middle East. At the same time, methods in measuring and quantifying the extents and scope of ancient monumental polychromy depended on parallel developments in the »hard sciences« which allowed for the scientific examination of the surface of ancient materials. Discoveries such as the seated scribe from Saqqara in 1850, the Augustus statue at Prima Porta in Rome in 1863, or the Korai statues on the Athenian Acropolis in the 1880's added to our knowledge in the 19th century, yet research on the surface of these monuments was limited to scientists working in fields such as conservation and chemistry and began often much later. By looking closer at conversations between excavators, museum curators and research scientists, this paper will introduce some key individuals in the discourse, reflect upon critical moments of discovery, and discuss ongoing developments and research in the field, which is shaped by a merging of disciplines. Overall, my contribution will call for a contextualization of the archaeology of ancient polychromies.